Arden Gatzke's Story ...

I grew up in a family of seven-my parents, Theodore and Amanda; my brother Harold "Tador"; and my sisters, Florence "Flo", Leona "Lee", and Mildred "Millie"-on a farm near the small Midwestern town of Ripon, Wisconsin, where I attended Ceresco Elementary School and graduated from Ripon High School in 1938.

Ceresco Elementary School Ripon High School

In 1939 I started working for Advertisers Manufacturing Company in Ripon. I operated a platen press, printing on cloth advertising products. After the war, I returned to the same company and worked there until 1952, when I went to work for Fabrico, a similar company in nearby Green Lake, Wisconsin. I retired from Fabrico in 1986.

I married my high school sweetheart, Betty, on 22 December 1945, and together we raised two sons and enjoyed grandchildren and great grandchildren. Betty died on 11 November 2005.

Betty Gatzke at the Ripon Historical Society Museum

Betty Gatzke at the Ripon Historical Society Museum"Helping the kids to learn about 100-year-old items in the kitchen" (May 2005)

It was from this environment of family, community, fresh air, corn fields, and dairy cattle that I was drafted into the United States Army on November 19, 1941, and inducted at Ft. Sheridan, Illinois. It was this family and this community that sent the frequent newspapers, packages, and letters that helped to maintain my ties to hope and home during my nearly four years away during World War II.

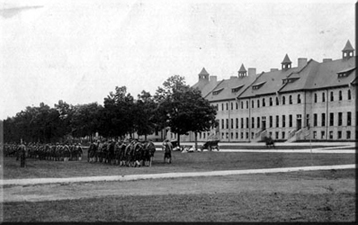

Ft. Sheridan Barracks, Wisconsin

Ft. Sheridan Barracks, WisconsinAfter eight weeks of basic training at Ft. Knox, Kentucky, I found myself being prepared to go to war in an M 4 Sherman tank. During 1941 and 1942 I received training and practice at Ft. Sheridan, Ft. Knox, Ft. Benning, Camp Sutton, Ft. Bragg, and Ft. Dix. I had to learn to do all the jobs necessary to keep the tank going. I could drive, repair, clean, and command the tank. Each tanker had to know how to do it all. We were a team. If we lost a member, we had to fill his place and do his job without hesitation.

Ft. Knox, KY Dec.1941 Camp Sutton, Aug.1942

We learned the other basics as well, like reading a compass and digging pits, running an obstacle course, blackout driving, shooting a variety of firearms, learning hand signals, and climbing down nets like they would have on ships for us in case the ship got hit. In the crowded living conditions in the camp we also had to learn as much as possible about how to keep from getting sick. After hours and personal chores, like doing laundry in primitive conditions, we could participate in the usual poker games, football, volleyball, and drinking.

Ft. Bragg, NC Aug.1942 Ft. Bragg, NC Sept.1942

On 11 December 1942, the time came for shipping out. We left Fort Dix on a train, followed by a ferry, and then on to Sea Train Texas. The tanks were already aboard. We left the dock at 9:00 the next morning. I was on submarine guard, which meant sitting by the rail of the ship up forward and watching for submarines. By December 13, we were in the middle of a storm producing waves twenty feet above and then twenty feet below me. Dishes flew everywhere, and most of the men were sick. I never got seasick. On Christmas Day, 1942, we landed at Casablanca, Africa. For the next six months we engaged in more preparation, getting our bodies, our minds, and our equipment in peak condition for what was to come.

The port of Casablanca, Africa

The port of Casablanca, AfricaOn 7 July 1943, we loaded our tanks and ourselves onto LCT 24, and the next day began our crossing of the Mediterranean Sea. During the trip we hit the biggest storm in fifty years. One sailor and I were the only ones not seasick. On Saturday, July 10, we invaded Sicily at Licata and began fighting Germans. It was my first battle. Two days later, Company G had three tanks knocked out. They were on one side of a hill and our Company H was on the other. We were eating watermelons and tomatoes growing there. War and peace were just a few hundred yards apart.

the Landing on Sicily, Italy

the Landing on Sicily, ItalyOn 11 November 1943, we boarded HMS Monterey and headed for England. We arrived in Liverpool on 27 November and the next day we settled in at Tidworth Barracks in Southern England, where we got additional training in chemical warfare and German language. In February I got an eight day furlough and went to London, where I stayed in the Battersea area and slept in an air raid shelter at night. On 8 February England was in complete blackout. No lights were showing anywhere. Tavern doors had blackout curtains several feet behind them so that when the door was opened no light could come out into the street. Just as I was walking by, someone opened the door as someone else opened the blackout curtains and I got a quick glimpse inside and realized it was a pub. I went in and spent a nice quiet evening. The next times into town I couldn't remember the name of the street the pub was on and was never lucky enough to be walking by as two people were going through the doors at the same time. During my six months at Tidworth Barracks, I had a number of opportunities to go sightseeing along with many more opportunities for training and practice.

the Theatre at Tidworth Barracks

the Theatre at Tidworth BarracksOn 4 June 1944, we made ready to leave Tidworth Barracks, turning in our English money for French. D-Day and the invasion of France was two days later. We left Tidworth Barracks in our tanks at noon and arrived in South Hampton about 1600 hours. After sitting around waiting all day on 7 June, we rode our tanks into LST 282 at 1300 on 8 June and headed out into the English Channel. I set foot on French soil for the first time the evening of 10 June. We put up our pup tents some distance from the beach, which turned out to be a good thing, since the Germans kept shelling and bombing the beach area all night long. Sunday morning, 11 June, we had to stand to at dawn. That meant that everything had to be on the tank ready to go into combat, so we stowed our tents aboard the tank and got the whole crew inside.

on the way in the M4 Sherman tank

on the way in the M4 Sherman tankThat afternoon we got orders to move from Moslem to Blay, about 20 miles. I saw my first dead German soldiers laying on the side of the road. We saw a lot of hand to hand fighting for a number of days after that, and had a lot of artillery fire come close to our tank. We left our attack position 26 July. We had to fight our way out for over ten miles, and Company H had our first fatality, Pvt. Burns. We continued to take heavy artillery fire and saw a lot more soldiers killed on the ground. We lost Henry Wellnitz to a piece of shrapnel in the neck, and that hit the whole company very hard.

Henry Wellnitz is buried at Brittany Cemetery, St James France

Henry Wellnitz is buried at Brittany Cemetery, St James FranceThe first four days of August we got a little time to rest and make repairs, and then we were back in the thick of battle again. We got a little bit of a break in early September because our tank was not running right and needed a new motor. French families fed us dinner for several nights. On 9 September the tank was ready to go, so we left. I drove the tank for 93 miles and then ran out of gas, so we got pulled for another ten miles. We went through Brussels, Belgium. By 13 September we were back with the company and back in the war, pushing to capture Winterslag. We were the lead platoon. We got into Mechelen 14 September and on 15 September we were again the lead platoon on the way to Eisden. After capturing the city we went back to Mechelen. On 16 September, along with the 99th Infantry, we fought our way between the Albert Canal and Meuse River, taking several prisoners. I was seconds away from death on several occasions.

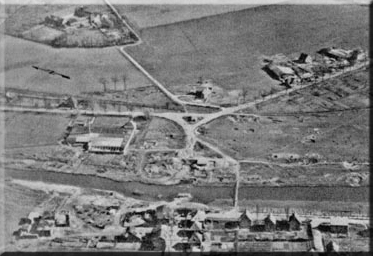

the Albert Canal near Hasselt (Belgium)

the Albert Canal near Hasselt (Belgium)By 20 September 1944 we had made our way to Beck, Holland, where we got a chance to relax a bit and watch movies. On Sunday I slept all day, but we were back into Germany soon enough. We returned to Germany on 5 October and were back into the bombs and artillery by 7 October. We attacked Bardenberg on 12 October and Würselen on the 15th. The fighting was heavy and went on for days. On 27 November we attacked Merzenhausen and the Germans counterattacked. We lost a tank, but sustained no casualties. The next day we attacked Barmon with the 41st Infantry.

Würselen (G) in November 1944

Würselen (G) in November 1944Early December gave us another chance to rest up and look at a lot more movies. I got some dental work done and got new glasses. On 22 December 1944 we moved out again and ended up in the woods near Ciney, Belgium. A couple of days later, as we started on a drive to Bussionville, my gunner took out a German car that was coming down the road, but the four occupants got out and ran.

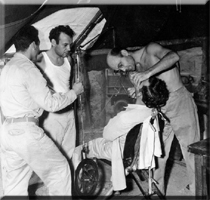

dental work during war (38th BG)

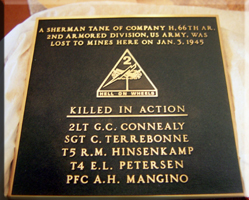

dental work during war (38th BG)Just before dark on that same day, our own Air Force mistook our column as German and straffed us with their 50 caliber machine guns, hitting my tank several times. On Christmas day, we were still taking fire from the Germans. They hit our tank and another one, so both headed back to Ciney. We had beer with our K ration Christmas dinner, which was more than the rest of the company got. We took the tank in to the maintenance company in Modave the next day. We slept with Belgian families while we were there and even got some hot water for a shave. We named our tanks "Homesick" and by this time we were on Homesick III. On New Years Day of 1945, Homesick III got a broken propeller shaft, so we were pulled by retriever back to Maintenance Company in Hailot. Meanwhile, Lt. Connealy and his four crew members were killed when Homesick IV hit a pile of mines. I lost some special friends. Homesick III was held up for parts, so I got Homesick V. On our way back to the front, we went past Lt. Connealy's tank. The bodies had been removed. We were under artillery and direct fire.

pulled back by retriever ...

pulled back by retriever ...By the time we started on the drive to take Samree and Hoffalize, there were only seven tanks left in the company. The artillery fire got so intense as we went over a slight hill that we started to back up behind the hill again. As we stopped all in line, a German gun or tank to our right opened fire and with four shots knocked out four of our tanks. My tank was next in line to be hit, but a wood was between the German and us and he couldn't see our three tanks that were left. We three tank commanders got out of our tanks and had a discussion on what to do next. As we turned to return to our tanks a mortar or artillery shell landed near us and knocked us all down. My glasses were all snow covered and bent. We picked ourselves up and got back into our tanks.

Harold Cook, John Fritz and TD Smith TD Smith's final resting place

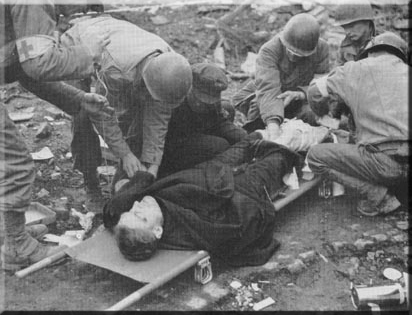

About five minutes later my crew asked if I could see anything by the other knocked out tanks. One was burning and the commander was caught half out of the turret. As I turned to look my whole body turned, not just my head so I told the crew I was going back to the medics. I got out of the tank and walked back across the snow covered field we had just come over until I came to the Company A 48th Medics about a half mile back. They discovered about a dozen pieces of shrapnel in my arms, chest, and neck. The doctor asked if I wanted to go to the hospital or back to the company. I said I would go back to the company. He then asked how long I had been fighting, I told him ever since D-Day plus 4. He said I wasn't going back to the company; I was going to the hospital for a rest. Six of our men had been killed on 3 January and six more on 6 January. Counting the two that had been killed previously the total was now fourteen killed.

Memorial Conneally the plaque on the Memorial

Lt George Conneally

Tec4 Edward Petersen

PFC Anthony Mangino these men found their final resting place at Henri-Chapelle (Belgium)

After a train ride with a nurse giving me shots every couple of hours, I arrived at the 217th General Hospital in Paris at 4:00 in the morning on 9 January 1945 with two very sore arms from all the shots. I left the hospital on 14 January on a train headed to Fontainebleau, France, where the 9th Replacement Depot was located. I got tommy gun training there. On 22 January I was on a train again, headed for the 3rd Replacement Depot. The train car was old and had no seats. It was called a 40 and 8 because during World War I these cars were used to transport either 40 men or 8 horses. This time I went to camouflage school and gas school, where I was supposed to learn about all kinds of gasses and protective methods so that I could return to the company and teach others. I was also a 75mm gun instructor.

a 40 and 8 train wagon ...

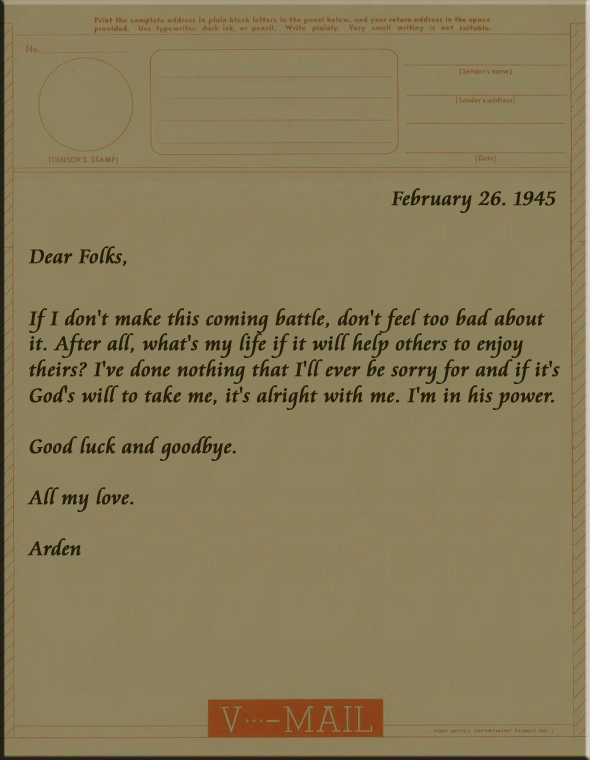

a 40 and 8 train wagon ...A truck ride took me to a new camp located by the borders of Holland, Belgium, and Germany. On 26 February 1945, as we were getting ready to move out, I sent the Corps and Division map they gave us home, along with the 2nd Armored Division History telling what we had done so far. I sent this letter with them: ...

We went through the town of Linnich, what was left of it, on 27 February. Every building had been destroyed. You could look from one end of the town to the other and the only thing to obstruct your view would be the two chimneys that were still standing. Everything else had been collapsed down to less than five feet. It was just a mess. We left the line of departure about eight miles south of Munchen-Gladbach, fought all day and stopped near Munchen-Gladbach that night. On 1 March we left Munchen-Gladbach and battled our way to Schiefbahn. I placed my tank next to the buildings on Main Street. One long block down the street some Germans in their jeep like vehicles stopped and talked to a group of civilians standing on the corner. I told my gunner to sight the 75mm to the left of the intersection so that when the soldiers left and made a left turn down the side street he should fire at them. But if they came toward us not to fire because then they would have no place to go as there were no more side streets between them and us. The first vehicle started and turned left. My gunner did not fire when I told him to. The second vehicle started and also turned left. I kept saying "Fire! Fire!" but he didn't. I was so angry I pulled out my pistol to shoot him, but it stuck. By the time I got it out the anger had disappeared. Lucky for both of us that the gun stuck. He said he just couldn't pull the trigger. Needless to say, I got a different gunner real quick!

the German town of Linnich ... destroyed by war

the German town of Linnich ... destroyed by warI found out later the infantry had captured all the soldiers and both vehicles. Then I talked to two old women sitting on the steps of their apartment. They were so happy the war was nearly over and that their town had not been destroyed. I got back into my tank and just then the Germans took a shot at my tank. They missed the tank but the shell killed one of the women and the other looked on in shock as her leg went rolling down the steps. I had my driver back my tank onto a side street and some people carried the woman into the apartment. I don't know if she lived or died.

As we sat on this side street facing the main street, another tank was backed up to us and sat watching the fields in front of them. Somehow the Germans must have come up behind the houses on the main street and got into position to fire a bazooka at us. I don't know where it hit on the tank but I yelled, "Let's get out of here!" and started drawing my pistol out of the holster as I was getting out of the turret. The gun hit the turret edge and went rolling down the front of the tank onto the pavement. When I reached the ground I reached down for the pistol and a stream of tracer bullets from a burp gun went between my hand and the pistol so fast it looked like a solid rod. I let the gun lay and the ten of us from the two tanks headed to the rear over backyard fences several feet high, with two Germans firing at us with their burp guns. After we reached safety we found one bullet hole in the tail of one guy's coat. All were safe and no one even got scratched going over the fences. My tank burned up. That was the only tank I lost to the enemy.

German soldiers with their MG42

German soldiers with their MG42Friday, 2 March 1945 I was given another tank. I was told it was ready for combat, but I didn't think it was, so I talked them into giving me the rest of the day to clean and fix it up a little. I spent all of the next day trying to get back to the company and finally caught up with them on Sunday, 4 March, as they were fighting through the fields and not on the road. I saw an enemy vehicle and had my gunner fire a round at it. The gun jammed, so I got out of the tank to get the ramrod to unjam it and there was no ram rod, so I went to the nearest tank to borrow one. It was the major's tank. I took the ramrod, cleared the gun, and replaced the ramrod on the major's tank. A short time later the tank next to me got stuck so I stopped to pull him out. Neither one of us had a tow cable so I went to the next tank to borrow one. It was the major again. So I took his cable, pulled the stuck tank out and returned the cable.

We got relieved from fighting for a few days between 5 March and 27 March and stayed in a house with a father and two daughters for several days. My driver and I took the tank to Maintenance. During this time I learned about the powerful effects of potato wine. I passed out on a quarter of a canteen cup full!

a picture of Arden in England, March 1944

a picture of Arden in England, March 1944On 27 March we moved out, and the next day we crossed the Rhine River on a pontoon bridge. By 31 March we were fighting day and night for many days. After we crossed the Wesser at Hameln, we ran into a bunch of Hitler Youth. These were young boys ten to fourteen years old. They were taught never to surrender and they didn't. We had to shoot them or run the risk of getting shot in the back if we went past them. It was very hard to do but it was them or us and we chose it to be them. We fought on and on, with no sleep. On 7 April we got to Edlendorf, where we saw sunshine for the first time since this drive began nine days ago.

Never been taught anything else, they died for the Führer ... Hitler Youth

Never been taught anything else, they died for the Führer ... Hitler YouthOn Friday 13 April we got two more tanks and some infantry to capture a town in front of Magdeburg. We liberated a displaced persons camp-slave labor from different countries-that was next to a warehouse full of whiskey. They filled our tank. The next day we finally got reunited with the company again at three o'clock in the morning. We rested in a pretty nice house in Magdeburg. A couple of days later I was sick, weak, and vomiting enough that I went to the 48th Medics. I had physical exhaustion. I put blankets on the floor of a big building with about a hundred other guys and went to sleep. I slept for forty-eight hours except for the four times I got up to eat for about ten minutes each time. I stayed with the medics for five days. In those last sixteen days of fighting we were lucky if we got a couple of hours sleep a night. I returned to the company on 22 April. A few days later our company got pretty drunk on the liberated whiskey. Two guys got in an argument and one got cut on the arm with a broken beer glass. The order came down to get rid of all the whiskey, so we lined the bottles up on a fence and shot them all up with our pistols, carbines, and revolvers. Lots and lots of whiskey got soaked up by the ground.

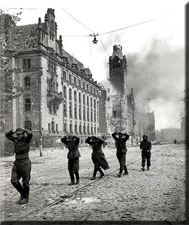

German POW's being escorted in Magdeburg

German POW's being escorted in MagdeburgOn 2 May I got "Homesick" back again and took it to C Company Maintenance. They drew names of people to go home, and I was one of the five names drawn that day. While at Maintenance I had my first shower in a long time. A little over a week later, I got a pass to go to Paris. We left on a truck on 15 May and stopped in Munster overnight. We saw bodies in tanks of brine that were used for experiments. We left Munster early the next morning and by early afternoon arrived at Vieviers, Belgium, where we caught a train for Paris. Once in Paris we settled in a hotel near Gare De Nord Station. The next day we took a bus tour past Notre Dame and other things and went to the Stagedoor Canteen, a hangout for soldiers on pass. We walked around Paris on Sunday and left on the night train back to Vieviers, where we caught the truck to Munster.

Arden Gatzke in front of his tank "Homesick"

Arden Gatzke in front of his tank "Homesick"We got new Eisenhower ETO jackets and sewed all our stripes and patches on them. We were to be in a parade on 24 May to receive Belgian and French citations. We also got a "Hell on Wheels" patch for our uniforms. On 18 June there was a Division ceremony where we were awarded the Belgium Fourragere.

the "Hell on Wheels" patch

the "Hell on Wheels" patchIn July we headed for Berlin. The Russians made us take a detour to get there. We rode in the tank for eighteen hours, 184 miles. We stopped for a couple of hours to fix two boggie wheels and ended up traveling alone. We finally caught up with the company in the suburbs in the Marienhof area. While in Berlin, we got a Presidential Citation, were in a parade, and had our company pictures taken. I took communion in a church with Hitler's symbols in it. I took a truck tour that included Hitler's house and the stadium where the 1936 Olympics were held. I saw President Truman as he rode by in a review for him on the Autobahn and a review for General Marshall, Admirals King and Leahy, and other French, Russian, English, and US high brass. We also saw a review for General Patton.

the Olympic Stadium Berlin in 1936

the Olympic Stadium Berlin in 1936On Sunday, 22 July, we got a truck into Hasselt, Belgium, where we went to the Café Cecile and drank a lot. We stayed overnight, leaving in the morning on a truck bound for Lebenstedt, where we spent the night in the home of a family. When we left Lebenstedt, the truck driver got lost and we ended up in Russian territory and had to do some tall explaining to get them to permit us back into Berlin.

Arden Gatzke in Lebenstedt (G), June 9, 1945

Arden Gatzke in Lebenstedt (G), June 9, 1945At the end of July it was finally time to go home. I turned in my clothing and began the trip with a truck ride of 325 miles to Arolsen, Germany. The next day we rode through Germany, Luxemburg, and into France, arriving at Thionville, France at midnight. We then went on twenty more miles to Conflans, France, where we relaxed and watched a lot of movies and didn't work very hard.

On August 13 I walked to the train and rode all night and all the next day, arriving at Camp Lucky Strike near Marseilles, France, on 15 August.

VJ Day came on 15 August. Japan quit! The war was over! Eighteen planes were sent from Marseilles to the Pacific to fly prisoners home, which left only nine for us. Only 270 men per day could leave instead of the usual 1000 a day. There was a 3000 man backlog. I figured I would be here at least ten days, living in pyramidal tents. We had stage shows and movies and inspections to pass the time.

Camp Lucky Strike with it's pyramidal tents

Camp Lucky Strike with it's pyramidal tentsFinally, on 26 August, I boarded the Liberty Ship General Bliss and left Marseilles that afternoon. After we passed the Rock of Gibralter and Tangiers the ship started rocking and guys started getting seasick. I was lucky. I never got seasick on any of the five voyages I took. We arrived in Boston, Massachusetts, on 4 September and went to Camp Miles Standish. We got clean uniforms, haircuts, opportunities for more drinking, and, of course, more movies. I called home on 6 September, and my brother Tador answered. I told him I'd be leaving for home the next afternoon. I left Miles Standish Friday afternoon and arrived in Chicago on Saturday afternoon. By evening I was at Ft. Sheridan, where I spent the night. Monday I was processing out all day and was finally discharged from the Army that night. I stayed overnight in Milwaukee with a high school friend named Bob Simmons and took the bus to Ripon on Tuesday morning.

the Liberty Ship General Bliss

the Liberty Ship General Bliss

REFLECTIONS

We have a college in our town, Ripon College. For a number of years one of the history professors,

Bill Woolley, assigned his students to interview people who had lived through World War II and write a

paper on the interviewee's perceptions of the war. An 18-year-old first year student named Richard Topping

interviewed me in 1995. I still have the paper he wrote, and I believe he captured my perceptions quite

well. The following reflections are excerpts from his paper.

To Gatzke the war was not a struggle between good and evil. He was not fighting against an ideology, but against time. He measured the war not in battles won, but in days survived until release…Questioned about an ideological identification with the war Gatzke referred to an incident that occurred during the Allied drive into Germany when his tank unit and infantry units met up with a group of Hitler's Jugend (youth). "It was a group of 12 and 13 year olds with rifles and bazookas, but if you walked by them, they'd shoot you in the back. It took three hours and the death of all the youths before the engaging Allied units could break through and take the town. What kind of ideological struggle involves killing kids, whether or not they are in Nazi uniform?"

"What kind of ideological struggle involves killing kids"

"What kind of ideological struggle involves killing kids"Gatzke saw the war as neither an effort to stop the evil Nazis, nor as an opportunity to participate in romantic battlefield excitement…The ideological battle was between governments, the actual fighting was between young men just hoping to make it home alive.

During battle the crew had to work together, like a machine within a machine, to keep the tank running. If a crew member was killed, the rest of the crew would have to compensate. This teamwork coupled with the uncertainty of life and death, turned the unit into a fraternal type organization.

Gatzke was wounded while in Belgium. After only 3 weeks he asked to be allowed to return to the front. He feared that if he waited too long that he would not be able to return to his own unit, but rather be reassigned to another one. It was this comradeship that gave most men, including Gatzke, the will to fight the war day to day. The men wanted to make it home, but make it home together.

Gatzke perceived the war as a situation that Company H was thrust into, and without teamwork they would never make it home alive.

The destruction became so commonplace that the troops became desensitized to it…"All the towns looked the same. By the time we got there they were usually reduced to rubble with a few dead bodies here and there, except that one time." That time Gatzke is referring to occurred after a town had been taken and his unit rolled in and stopped to eat. The men ate a combination of K-rations and tomatoes from a garden that had not been destroyed. But the gravity of the story comes not from the lunch, but from the fact that the troops ate not 20 yards from the bodies of several Germans who had been killed by a flame thrower earlier in the battle. Their bodies were shriveled up into little black masses. Chickens were picking at them, they were the only food around. "I didn't think twice about it," says Gatzke. But the fact that 50 years later Gatzke still remembers that lunch would suggest that Gatzke thought a lot more about it than his memory recalls.

Asked when the war changed from a present experience to a past memory, Gatzke answered, "It is still not over. The war has never ended for me…I still have dreams." …Because what Gatzke experienced is so difficult to derive a meaning from he was forced instead to find meaning within his unit and his buddies.

The actual war Gatzke fought is the one that still rages in his subconscious mind. It is as unfacable now as it was then. The war Gatzke fought possessed neither the simplicity nor the patterned logic that his perception recalls. The war was a mass of senseless destruction and slaying…The good and the bad died equally. Sometimes it seemed like the good died more often. Being a good soldier and doing your job gave no guarantee that you would live. No one knew. Day to day, hour to hour, minute to minute, there was no sense to it. Some men, like Gatzke, survived the whole war, others died on their first mission, and still others died on their way to the lines. The value system of a combat soldier became so different from what he had known previously that he latched onto the only thing that he could make sense of, staying alive and friendship.

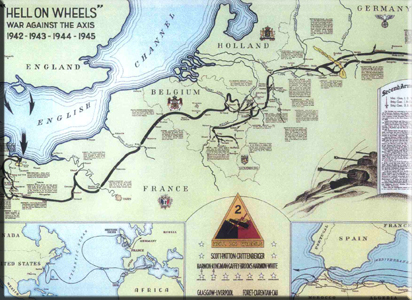

The map below shows the road the 2nd Armored Division went during WWII. Arden Gatzke was there all the way ... (Click the map to enlarge !)

These days Arden Gatzke lives in Ripon, Wisconsin. Arden is a volunteer at the Ripon Historical Society.

Arden Gatzke in front of his home in Ripon ...

Arden Gatzke in front of his home in Ripon ... still stuck to the Hell on Wheels

published May 13, 2006