George Miller's story ... told by himself

My four years in the Army of the United States, 1941-1945, turned out to be the defining experience of my life. I had grown up in Evanston, Illinois, a quiet, peaceful suburb of Chicago enjoying all the advantages of a loving family, good friends, and good schools. I was looking ahead to a life much like that of my businessman father.

George Miller in his early days & Fountain Square, Evanston 1923

The outbreak of World War II in Asia in 1937 and Europe in 1939 seemed far away and unlikely to change my life in any way. But, of course, it did. Because the war was a growing threat to the United States, our Congress passed a Selective Service Act in 1940 that established something like universal military service. In November of 1941, after graduating from college, I was called up for training in the Army. It was supposed to take eighteen months. Three weeks later, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese navy bombed our naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and we were in the war.

December 7, 1941,

the Japanese navy bombed our naval base

at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii

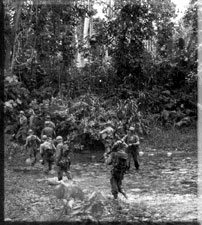

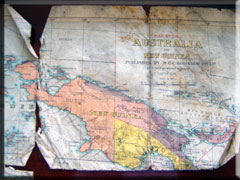

After thirteen weeks of basic training, I was assigned to an infantry division already on alert for shipment overseas. Our destination was Australia, where we continued our training and then went to the island of New Guinea to engage the Japanese forces that had established a foothold on the island.

Landings on the island of New Guinuea

New Guinea is a very large island immediately north of Australia. At that time the eastern half was part of the British Empire; the western half was part of the Dutch East Indies. There was only one real city on the island; the rest of it was mountains and jungle inhabited by Melanesian natives still living in the Stone Age.

the rest of it was mountains and jungle ...

It was as far removed as it could be from the kind of environment I was accustomed to. It is just south of the equator, infested with tropical animals, bugs, and diseases, including malaria, "jungle rot" (an ugly skin disease), and dysentery. Add to this the presence of the Japanese Army that had every intention of taking the island for its own purposes and you will see that our lives were not quiet and peaceful. I don't mean to make light of the horrors of war, but it occurred to me at the time that both sides were thousands of miles from home, fighting over an island that neither of us wanted. War can be as senseless as it is cruel.

"War can be as senseless as it is cruel ..."

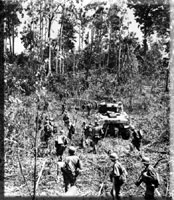

I was a machine gunner to begin with; later I became a machine gun squad leader and then a section leader of two squads. We moved along the northern coast of New Guinea, making amphibious landings where the Japanese had established bases. Our mission was to knock out these bases and clear a pathway for our navy and air force. We were part of General MacArthur's force heading for the Philippine Islands. In April, 1944, we crossed into Dutch territory and for a time we were paid in Dutch money even though there was no place to spend it.

Machine gun training & Machine gun in combat

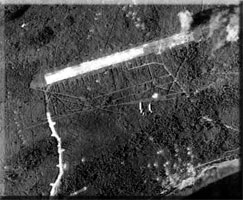

Our toughest fighting was on Biak Island off the coast of Dutch New Guinea where the Japanese were building a major air base. It was nothing more than a huge lump of coral virtually without fresh water and without any natives as far as we could tell. But coral rock makes a good foundation for air strips, so the island was considered valuable by both sides. But not to the infantry assigned to take it. The rock-hard ground was almost impenetrable for our entrenching tools when we tried to dig fox holes, which was our constant occupation. There were numerous deep caves in the coral cliffs, but the Japanese had gotten there first and had occupied many of them. They fought fiercely to hold onto them.

the air strip on Biak Island & fighting on Biak Island

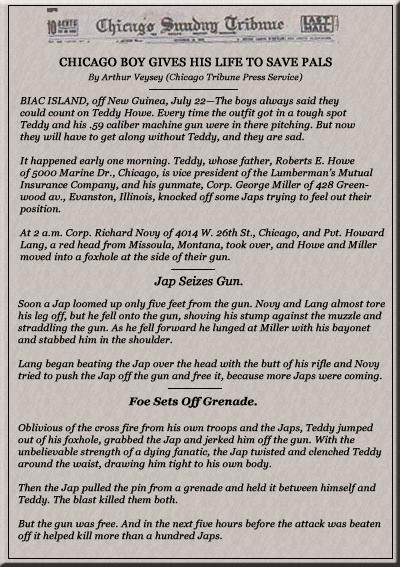

I had been very lucky in our previous engagements, but on Biak, finally, I was wounded and sent to a hospital behind the lines. My friend Teddy Howe lost his life. My father saved the newspaper story, and I still have the clipping that describes that day.

I had a rather long stay in a series of hospitals and was never sent back to my unit. In December of 1944 I was "rotated" home to the United States where I served until the war's end in August of 1945.

the end of War ...

Armed conflict is not a pleasant experience in any sense of the word. Sometimes there is a feeling of exhilaration when things quiet down and you realize that you are still alive, but the loss of a friend can offset that. The constant sense of danger during an engagement is not exhilarating. The confusion of battle is very unsettling; there is no way of knowing what's happening beyond your own limited line of vision. And, of course, the noise adds to the confusion.

the maps George carried with him throughout the war

Yet there were positive aspects to my military service as a whole. I had lived a sheltered life before December 7, 1941. In the four years that followed I got to know myself and my fellow man a lot better. I served with men from all over the United States and Australia. They weren't all saints, but there was something worthwhile in most all of them. I found that I could work with them, teach them, and even lead them. For the most part they had been denied the kind of education that I had had, but they seemed to see the value of it. While convalescing after being released from the hospital I had an opportunity to serve in the Information and Education section on the base, lecturing to the new replacements on their way to the war zone. I enjoyed it. I had found my mission in life.

training replacements at a WWII Base ...

After my discharge from the army I returned to school at the University of Michigan. With the help of the G.I. Bill of Rights, a government program for former service men and women that offered a month of education in a qualified institution for every month of active service up to four years, and at no cost to the student, I was able to get the necessary post graduate work for my chosen occupation. I emerged with a doctorate and began a career as a professor of history.

George as a professor at Ripon College

hes's flanked by buildings from the University of Michigan

(Museum & Law School)

My life as a professor of history has been stimulating and rewarding. After three years at the University of Michigan, a large state school of about 12,000 students, I moved to Ripon College in Wisconsin. Ripon is a small liberal arts college whose classes are small and informal. It turned out to be just what I was looking for. So Ripon, a small city of about 7,000 people, became home. I taught there for twenty-seven years and have remained there for twenty-five more years since retirement. I have written or edited three books on American history and have been active in the Wisconsin Historical Society, a state agency concerned primarily with public education. I am active in the Ripon Historical Society, serving on its board of directors and as an archivist and reference resource. I still have regular contact with Ripon College as a mentor and team teacher for students and interns interested in public history, archives, and museum work. A decision made many thousands of miles from home, in the midst of a terrible war, turned out to be exactly the right one.

Ripon Historical Society

Ripon Historical SocietyGeorge picked up his life after the war and in fact the war shaped him into who he is today. A respected citizen who lived his life teaching future generations ... Meanwhile his buddy Ted Howe, who was killed on Biak Island on 22 June 1944, was brought to the Island of Manila where he found his final resting place between 17.100 men and women who shared his fate ... George never forgot his buddy Ted and still treasures his memory ...

Ted's final resting place in Manila

Ted's final resting place in ManilaPFC Theodore P Howe, rests in Plot D, Row 1, Grave 166 ...

In Memoriam Ted Howe ...

published March 19, 2007