Charles William's story, told by his Newphew Kevin D Klump ...

Charles Williams, Jr. was born on March 28th, 1921 in the small village of Butler, Illinois. The oldest child and only son of Charles and Bertha Williams, he was big brother to two younger sisters, Lorena and Betty. .

Charles age 14 & Charles with his parents Charles and Bertha

Charles age 14 & Charles with his parents Charles and Berthaand his sisters Lorena and Betty

In his younger years, he was a member of the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), a work relief program for young men from unemployed families. After leaving the CCC, he was hired as part of a section crew for the New York Central Railroad and most likely held that position until he was drafted. He married Irene (Brown) Williams on August 24, 1940 and became daddy to Irene's daughter Marla Mae.

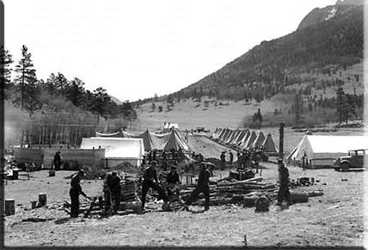

a Civilian Conservation Corps camp

a Civilian Conservation Corps campCharles was drafted and inducted into the United States Army on December 14, 1943. Shortly thereafter, he was sent to the Infantry Replacement Training Center in Anniston, Alabama where, for the next 18 weeks, he would call Fort McClellan home.

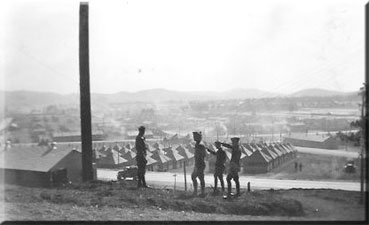

Tara Hill - Fort McClellan

Tara Hill - Fort McClellanAfter finishing his basic training, Charles was issued a 7-day furlough, which he used to return home to Butler, Illinois to see his family before leaving for Europe. It is unknown precisely when and from where Charles embarked for Europe and it is also unclear as to where he disembarked overseas. He was assigned to K Company, 3rd Battalion, 112th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division of the U.S. First Army.

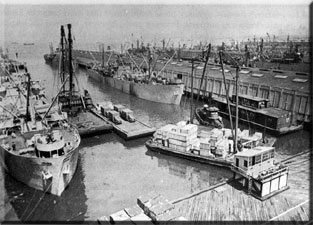

part of the New York Port of Embarkation

part of the New York Port of EmbarkationLittle is known about his service prior to his death. However, it can be said that he was part of the 1st Army's drive from Northern France, through Belgium and Luxembourg and into Nazi Germany. During their movement toward Germany, the 28th Division saw battle at places like Percy and Gathemo in August. The 28th then found itself in Versailles on the 28th of August and were given the honor of being the lone Infantry Division to march down the streets of Paris.

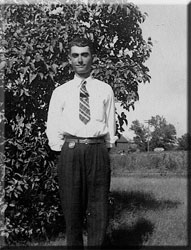

Charles in 1943

Charles in 1943Following the parade, the Division was encamped at Bourget Field, the same airport where Charles Lindberg landed in 1927. From Paris, Charles and the rest of the 28th Division began its push toward German soil.

Victory parade of the 28th Infantry Division

Victory parade of the 28th Infantry DivisionParis, August 29, 1944

Standing in their way was a densely wooded area about one-half mile from the village of Germeter. It was on the 1st of November, 1944 that Charles found himself in the Hürtgen Forest. Thick with dark fir trees standing seventy to one-hundred feet tall, the Hurtgen Forest was so densely interwoven that it obscured the sky. On November 2nd the 3rd Battalion, of which Charles was a part, attacked the village of Vossenack at 9:30 in the morning. When the battalion tried to move forward, it was like walking into hell. From their bunkers, the Germans sent forth a hail of machine-gun rounds, rifle fire and mortar shells. The GI's were caught in thick minefields and their attack, although initially successful, soon stalled.

the church of Vossenack - 1944

the church of Vossenack - 1944They would pay for what ground they had taken. The position they held was not a good one; located on a ridge that one man said "made us stick out like a sore thumb", they were under constant artillery fire from German guns located on higher ground east and northeast of Vossenack. On November 3rd, orders came down to the Battalion to hold all objectives previously reached and protect the east flank of the Division. This meant that elements of the Battalion, including Charles' K Company, would be shifted to a defensive position located between the two villages of Schmidt and Kommerscheidt.

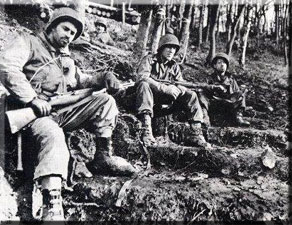

GI's resting in the Hürtgen Forest

GI's resting in the Hürtgen ForestIn the pre-dawn hours of November 4th, the Germans launched one of the most intense artillery barrages of the war. Their targets were the Allied defensive positions between the two villages. The U.S. troops here were shelled mercilessly for three solid hours. Soon after, enemy tanks from the 116th Panzer Division came roaring into Schmidt, followed by large forces of foot soldiers from the German 89th Infantry Division. Elements of the 3rd Battalion had no choice but to fall back, ending up in Kommerscheidt. Those who were not lucky enough to have escaped the enemy counterattack were cut off near Schmidt. Among these unlucky men were Charles and other men from K and L Company.

American tanks near Kommerscheidt and Schmidt

American tanks near Kommerscheidt and SchmidtForced to fight isolated actions against the heavy German advance, they would be pinned down in the woods southwest of Schmidt for the next 4 days. On November 5th, Division sent down orders to move tanks down a road called the Kall Trail, but no staff officer had gone forward to assess the situation in person and, in fact, the trail was nothing but solid mud blocked by felled trees and disabled tanks. Sadly, this led only to more needless casualties suffered by U.S. troops.

American tanks moving up the Kall Trail

American tanks moving up the Kall TrailWednesday, November 8th, 1944 dawned with cold, rain and yet another attack from the Germans against the trapped and embattled men from Companies K and L. Forced to finally admit that the fighting in this area was useless, Battalion commanders ordered the withdrawal of the men from Schmidt and the neighboring town of Kommerscheidt. Under horrendous fire from German guns, the remnants of Companies K and L slowly made their way to a staging area in the rear. Here, the exhausted men would mend their wounds and count their numbers. In all, more than 300 troops had been extricated from the area of Schmidt and Kommerscheidt, but Charles Williams, Jr. was not among them.

GI's trying to find their way in the Hürtgen Forest

GI's trying to find their way in the Hürtgen ForestLittle is known as to what exactly happened to the surrounded men from K Company during their withdrawal from Schmidt. Captured German papers entitled "Orders of the Day" stated that 133 of these men had been captured on November 8th. The rest, they reported, were annihilated. Before dawn on November 9th, three men from the trapped group of K and L Companies returned to the Division and reported that, when they left their fellow troops two days prior to look for help, the men had neither water nor rations and were under heavy enemy mortar and artillery fire. Finally, they stated that the possibility that any were still resisting the enemy was remote.

Advancing and retreating through devasted villages

Advancing and retreating through devasted villagesOf the thousands of casualties taken in this area, many were initially listed as missing. No doubt due in large part to the hasty withdrawal and the poorly coordinated execution of the retreat. Sadly, Charles' fate was not known for quite some time, even by those in his own unit. Over three months after Charles was not accounted for, the Regimental Chaplain, Richard I. Brown, wrote a letter to Charles mother. In the letter he simply expressed his deepest sympathy and that of the rest of the men in Company K, as well as his regret that he could not provide her with any definite news about Charles.

better times ... guarding German prisoners of war ...

better times ... guarding German prisoners of war ... On November 27, 1944 Charles' wife received word that her husband had been listed as missing by the U.S. Army. Some time after that a letter arrived from Charles dated November 1, 1944, arguably the last letter he ever wrote to his family. Just what the letter said or what became of it is yet another mystery unsolved, since both Irene and her daughter Marla have since passed away and no one knows where they lived prior to their deaths. Finally, in March of 1945, word arrived in Butler, Illinois from the War Department. It was the unthinkable. According to the letter from the Adjutant General, a corrected report just received stated that Pfc. Charles Williams, Jr. who was previously reported missing in action was killed in action in Germany.

the newspaper articel on Charles' death

the newspaper articel on Charles' deathIt would be nearly 2 more years before word would reach home

with regard to what exactly took place near the small German town of Schmidt on November 8, 1944. Charles mother had

apparently written to the War Department several times, the last being in April of 1946, in an attempt to learn precisely

how her son lost his life and where his remains lay.

Finally, on September 17 of that same year, she received a

letter from the War Department stating that "during operations to capture the town of Schmidt, Charles and other members

of his organization were ordered to retreat. Since he was not present for the reorganization of the unit, he was listed as

missing in action. Later, a casualty message was received from the Commanding General of the European Theatre of Operations,

stating that Charles was, in fact, killed in action on November 8, 1944, the same day he was listed as missing. Further

information showed that his death was the result of a severe shrapnel wound of the hip. However, nothing was found of record

to indicate whether or not his death was instantaneous."

thousands are still missing

thousands are still missingWall of the Missing in Margraten (Netherlands)

No one will ever know what Charles and the thousands of other fallen men endured during their fighting in Europe. In fact, no one who has not known war first hand can ever truly understand it. The men who were there and survived have to be willing to tell us what it was like. And we, the beneficiaries of their bravery, have to care enough to listen and remember their sacrifices.

thousands of other fallen

thousands of other fallenFor some of those lucky enough to have lived through it, homecomings must have surely been bittersweet. Being home with loved ones and in familiar surroundings may not have been much consolation to them, knowing that many of their comrades would not be coming home. And for Private First Class Charles Williams, Jr., serial number 36779848, First United States Army, 28th Infantry Division, 112th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Battalion, K Company, there would be no such homecoming. He is still there. Like so many other young men who laid down their lives for the freedom of others, Europe is his final resting place. Though he may not have come home; though he died in a strange land and was never given the chance to properly live his life, he lives today in the hearts of all who remember him.

Most people will never know what it's like to sleep in a cold and muddy foxhole; or sit behind the controls of a fighter plane; or man an anti-aircraft gun on the deck of a battleship. Most people will never know what it is like to face death on a daily basis. So, we are left with only our imagination… and knowing that our freedom as a people is secure because of men like Charles. He and countless others have bought our freedom with their lives… and we will most likely never be able to repay that debt. Keeping them in our memory and being grateful they were all there when we needed them is the only thing that really comes close.

If you ask a veteran of WWII why he went to war, they will most likely answer in much the same way as one veteran did. He said, "I did it to protect two things… my country and the lives of the people I love."

If Charles were alive today, I am certain that he would echo those sentiments. In the few letters the family has from him, he never wrote of the hell he and the others must have surely been living. Perhaps it was because of War Department sensors, but I am positive in thinking that it was his way of protecting the people he loved.

Though I never had the privilege of knowing my uncle, my mother, Charles sister and last remaining member of his family, has kept his memory alive in my mind and in my heart since I first showed an interest in who he was and what he did for me. I've often thought about what I would say to him or the questions I would ask, had he lived. And though he has been lost to our family for 63 years, I think we have all mourned his death at one time or another. But as strange as it may sound, perhaps we shouldn't.

General George Patton, when asked about his deep affection for those men who were killed in battle, said something very profound. He said: "It is foolish and wrong to mourn the men who died. Rather we should thank God that such men lived." I do thank God that men such as my uncle lived to secure my freedom and the freedom of the oppressed peoples of Europe during WWII. It is my intention to one-day travel to Belgium and visit his grave.

painting of General George S Patton Jr.

painting of General George S Patton Jr.In contemplating what I would do once I stand before the

engraved cross that marks his final resting place, I can only think of two words that would be most appropriate.

"Thank you."

These days Charles William Jr. rests in the beautiful American Military Cemetery at Henri-Chapelle ... He is remembered and honored by his nephew Kevin D Klump, by his entire family, by Nicolas Debey and his mother Francoise who adopted his final resting place, by every visitor of the Henri-Chapelle cemetery and by everyone who visits the In-Honored-Glory website.

a picture of Charles' final resting place will appear here shortly

a picture of Charles' final resting place will appear here shortlypublished February 21, 2008